How will the National Education Policy 2020 change higher education?

HOW WILL National Education Policy 2020 CHANGE THE GAME?

India’s children are schooling and not learning. As the recently-released Draft, National Education Policy (NEP) states, “India now has a near-universal enrolment of children in primary schools. Gender parity has been achieved and the most disadvantaged groups have access to primary schools.”

Yet, at the current time, there is a severe learning crisis in India, where children are enrolled in primary school but are failing to attain even basic skills such as foundational literacy and numeracy. The harsh reality is this: schooling is not learning. Strengthening education in India requires the new government to recognize the urgency of this reality and the gravity of India’s learning crisis. India needs to ensure, in mission mode, that every child in grade 5 has achieved foundational literacy and numeracy.

Understanding the Problem

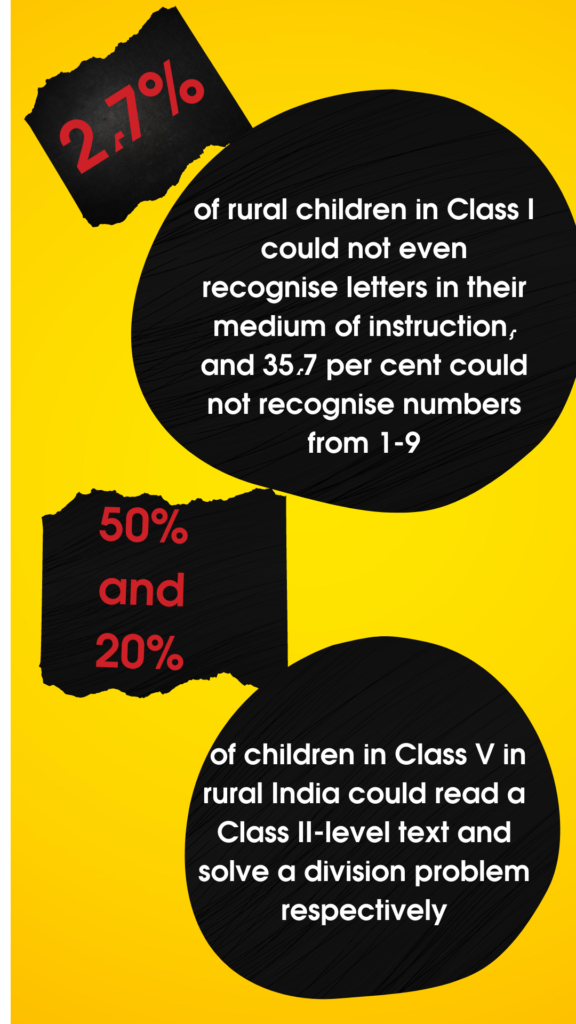

India’s learning crisis is a widely acknowledged fact. Since 2005, the Annual Survey of Education Rural (ASER) has served as a repeated reminder that barely 50% of students in standard 5 in India can read a standard 2 text. Several other studies, including the government’s own recently conducted National Assessment Survey (NAS) 2017, point to low levels of learning.

This crisis begins in the early years of schooling. Moreover, learning profiles are flat. In other words, if a child falls behind expected learning levels in the early years of schooling, sitting in classrooms, year after year, and progressing to higher grades does not ensure that the child catches up. Even the simplest skills like reading a simple passage remain out of reach of an alarming number of students. Drawing on a series of rigorous studies of learning profiles in India, economists Lant Pritchett and Amanda Beatty estimate that four out of five children who go into a grade not able to read will finish the grade still unable to read.[i] Even as children struggle with basics, the curricula and associated textbooks are designed in the expectation that children have acquired grade-level skills and can progress onwards. Pritchett and Beatty refer to the phenomenon as the ‘negative consequence of an overambitious curriculum’.

Additionally, several studies highlight that there are wide variations in student learning levels within a classroom. In the 2018 ASER survey, in the average standard 3 classrooms in Himachal Pradesh, 15.5% of students could read words but not sentences; another 24% could read a standard 1 text while 47.4% could read a standard 2 text.[ii] The result is a significant divergence between rates of learning and curriculum expectations. Another study by Muralidharan and Singh, with a sample of 5000 students spanning grades 1-8 in four districts of Rajasthan, finds that the average rate of learning progress across grades is substantially lower (about half) than envisaged in the syllabus and curricula. As a result, the vast majority of students struggle to cope and in the process learn very little.[iii]

Against this background, the focused, goal-oriented push for achieving foundational literacy and numeracy in elementary schools strikes at the heart of the problem. As the NEP emphasizes, ‘the rest of the Policy will be largely irrelevant for such a large portion of our students if this most basic learning (reading, writing, and arithmetic at the foundational level) is not first achieved’.

Moving from Policy to Action

The NEP offers an important starting point to develop a mission mode, goal-oriented approach to improving foundational skills in India. It also offers a fairly detailed set of powerful policy ideas, from redesigning curriculum to a national tutors’ program, teacher training, and community participation. But achieving these goals is not just about policy direction. Rather, it is about shifting mindsets and changing institutional culture. This can only be achieved through a fundamental overhaul of how elementary education is financed and governed.

The reality is that in its current architecture, the education system is designed and incentivized to cohere around the goal of schooling inputs (enrolment, access, infrastructure) rather than learning. All planning, financing, and decision-making systems are aligned to this goal. To

illustrate, annual plans, targets, and budgets are delinked from the articulation of learning goals. Instead, they are based on infrastructure goals determined through U-DISE (Unified District Information on School Education), a specifically created database for critical education indicators other than learning. Recent efforts to measure learning outcomes at the district level, such as the NAS, are not integrated into the planning and budgeting cycle.

As a result, plans have little to do with learning needs, and interventions specific to improving learning outcomes command relatively paltry money. In 2018-19, quality-specific interventions accounted for a mere 19% of the total Government of India (GoI) budget for elementary education.[iv]

Schooling goals inevitably privilege hierarchical, top-down delivery systems that seek accountability through easily verifiable, logistical targets (number of classrooms built, statistics on teacher qualifications, etc.). This attitude has permeated down to the classroom. Easy-to-measure metrics, ‘syllabus completion’, and ‘pass percentages’ have held our classrooms hostage.

The result has been a deeply centralized education system in which the central government determines priorities, rather than privileging school/student-specific learning needs; this leaves the entire education bureaucracy busy collecting information and monitoring targets relevant to New Delhi rather than schools and children.

Altering this schooling culture is not a simple matter of changing syllabi and textbooks, introducing new pedagogy, and improving training. It requires a complete overhaul of the organizational structure and associated incentive systems in which education stakeholders, from bureaucrats to teachers and parents, are embedded.

The education architecture needs to move towards a bottom-up, decentralized delivery system, which privileges the classroom and its specific learning needs. This will make the implementation of NEP’s specific recommendations a reality. The transition to a decentralized system can be achieved through the following key reforms.

Improving the Financing of Education

Despite being on the concurrent list, elementary education financing is disproportionately dependent on central programs. This is because most of the states use the bulk of their own finances (up to 90% in some cases) towards payment of wages and liabilities.

Thus government schemes (such as Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, now renamed Samagra Shiksha) are the only source of funds available to states for non-wage expenditure. These schemes privilege an extremely centralized, one-size-fits-all, schooling-focused planning, budgeting, and decision-making system. States, in this architecture, have little room for orienting spending to their specific learning needs.

From tied line-item funding to block grants

The first step towards shifting to an education system that prioritizes foundational learning is to overhaul the G.o.I financing system. One way is by putting states in the driver’s seat and providing them with flexible financing aligned to the achievement of clearly articulated learning goals. Specifically, the government should create a new funding window for foundational learning that gives states two untied grants.

The first untied grant would be for states to meet school infrastructure requirements. The Right to Education Act (RTE) mandates that all states meet a set of infrastructure and teacher norms. States should estimate their infrastructure requirements over a three-year period, which the Centre can fund annually.

The second grant should be a formula-based, untied learning grant financed over a period of three to five years. Funding through this window should be based on a long-term learning strategy articulated by state governments and linked to clearly articulated annual learning goals. Since this is an untied grant, the Centre will no longer need to busy itself with negotiating line-item expenditure. Rather, it can focus on providing technical support and guidance to states.

From an annual to a three-year planning and funding cycle

In the current annual government financial and administrative cycle, it takes a minimum of six months – usually up to November (well into the school year) – for money to move and new programs to be implemented. This is a result of long administrative processes linked to getting plans and projects approved, procuring materials, and finally ensuring funds reach their final destination.

Studies by CPR’s Planning, Allocations and Expenditures, Institutions Studies in Accountability (PAISA) point out that the bulk of the money usually reaches schools and districts midway (and often at the end) of the annual financial year. Consequently, programs have a late start, and also an early end to meet year-end financial needs. This needs to change.

The planning cycle needs to move away from an annual cycle to a three-year cycle (with annual financial approvals) so states, districts, and schools can plan better and ensure continuity in implementation.

Improving the Assessment System

To institutionalize a culture of accountability and ensure that states have access to and utilize regular, reliable data on learning outcomes, a significant effort will need to be made to improve the quality of data collection on learning-related indicators.

An important start has been made through the restructured NAS implemented in 2017 and the NITI Aayog’s School Education Quality Index (SEQI). However, there are several gaps. The current tools are linked to the achievement of grade-level competencies. But to be useful, especially at the school level, what they need to capture are gaps in foundational literacy and numeracy. This will enable teachers and planners to assess how far students are from these basic skills.

Without this critical data point, states are unable to determine the level at which to orient their learning levels. In sum, for assessments to be useful in addressing the learning crisis, they need to be aligned to foundational learning skills and not grade-level learning outcomes.

Further, the quality of data collection needs to improve. The NEP has recommended setting up a Central Education Statistics Division. This recommendation must be implemented urgently.

Moving beyond States to Districts and Schools

An education system decentralized to states is simply too large to effectively respond to the diversity of learning needs in schools and classrooms. In recognition of this, education policy has, on paper, made the district the unit of planning. However, traditionally, districts have little flexibility in making plans or control over the budget.

If the education system is to genuinely move towards a focus on classrooms and students, this has to change. Just like states, districts too ought to articulate learning goals over a period of three to five years, and have the flexibility to develop plans to meet these goals.

To incentivize districts, GoI and states could create a learning improvement fund that interested districts could compete for.[v] However, doing this will require a massive capacity building effort by the state and Centre to empower districts to make plans.

An interesting parallel is Kerala’s People’s Plan of 1996 in which the state planning board launched a year-long campaign to work with the Panchayati Raj system to develop the first-ever ‘people’s plan’. The central government could create a small capacity building fund for states to develop a similar plan campaign. Of course, an effort such as this must not be restricted to districts and should be extended to schools and parent-led school committees as well.

Teaching at the Right Level

Indi’s learning crisis has two challenges. The first is to ensure that students entering the school system do not fall behind in the first place. An important suggestion in the NEP that must be implemented is to integrate pre-school learning with the formal elementary school system. Further reforms related to curricula and teacher recruitment, training, and performance management will likely help redress problems encountered within schools.

However, the second and arguably greater challenge relates to students already in school, many of whom desperately need to catch up. For this cohort of students, there is today a significant body of evidence suggesting that efforts to match classroom instruction to student learning levels (rather than the traditional age-grade matrix), or ‘teaching at the right level’, implemented in mission mode, can result in significant and relatively speedy gains in foundational learning levels.

Many state governments and even individual districts today are beginning to experiment with implementing versions of teaching at the right level (TARL) in their schools. These efforts need to be supported and scaled up with both technical and financial resources. To do this, a specific FLN fund and technical partners at the GoI level could be established for districts to draw on to implement the TARL initiative.

This could be linked to the NITI Aayog’s Aspirational District Programme to ensure high-level buy-in and institutional convergence at the GoI level. Efforts to assess foundational learning levels, using ASER-like tools, are already underway. These need to be scaled up now.

From Assessments to Learning and Doing

One of the most damaging consequences of a centralized, schooling-focused implementation system is that it has undermined the professional roles of teachers and school-level administrators, casting them as passive rule followers, collecting data, and implementing orders from the top. It isn’t uncommon for teachers in schools to describe

themselves as mere clerks in an administrative system, taking them away from their primary teaching responsibilities. This view is reinforced by the fact that the career ladder for teachers – as they move to become headmasters, cluster- and block-level officers, and finally district education officers – is primarily focused on administration rather than supporting teaching/learning.

Recognizing this problem, the NEP pushes for reducing administrative work and improving teacher training and support infrastructure.

But these reforms will only work if they are accompanied by a significant cultural shift in how education reforms are debated and implemented. This shift must place teachers and frontline officers at the center of the attempt to reshape classroom pedagogy.

Consider this: in the last three years, significant efforts have been underway to move the needle on measuring learning outcomes. These include the NAS and SEQI referred to earlier. However, none of these assessments are geared towards the teacher or frontline administrators – such as the cluster resource center coordinators and block resource persons charged with mentoring and providing academic support to teachers.

These assessments thus merely function as tools for monitoring performance rather than as diagnostic tools that can strengthen the pedagogical support structure for teachers, motivate them, and assist them in improving teaching practices. For teachers and frontline administrators, this merely reinforces the view that they are no more than disempowered cogs in the wheel, primarily expected to follow orders and complete administrative tasks